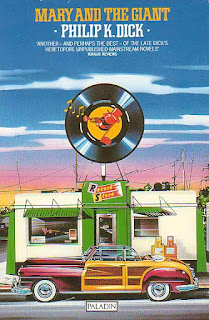

Mary and the Giant, by Philip K. Dick, 1988.

Mary and the Giant is one of Philip K. Dick's nine surviving mainstream or realist novels. These were written in the 1950s but for the most part not published until after his death in 1982, Dick's other 36 novels were science fiction. The mainstream novels are underrated and underread, in my opinion. But usually only those who have exhausted the SF novels will venture on the path less traveled by into obscurer PKD.

Mary and the Giant, like the other mainstream novels, is a realistic evocation of the 1950's, a time as strange, in retrospect, as any we might find in an SF novel--which is sort of the point, really, about why we should read these books. They evoke a sense of mystery and otherness--only here, instead of making the otherness explicit by using SF memes--androids, time travel, dystopias, and the like -- here the otherness stays largely hidden and only hinted at.

The characters here are connected in terms of being in the music scene of a small northern California town. No heroes and heroines here: this is about their relationships, and their errant and fugitive attempts of awkward groping for love with each other in various combinations. The racial and sexual frankness of the book is extraordinary for the time period in which it was written, which may partially account for why it was not published at the time.

The giant of the title, Joseph Schilling, arrives in town to open a classical record shop. His origins are mysterious: "Perhaps he had come all across the world; perhaps he had always been coming, moving along, from place to place....He was so immense that he towered over everything." This mythic description introduces a note of fantasy into the drab small town setting.

Mary Anne Reynolds (of the title) is a very confused young woman who bats around ceaselessly from lover to lover, apartment to apartment, job to job. Joseph briefly becomes her employer and would-be sugar daddy. Although he appreciates her as a free spirit, the match is hopeless because of her headstrong and dilatory nature. Also, because she was sexually abused by her father, an older man like Joseph cannot be other than toxic to her.

Joseph is mysteriously drawn to her,like to a femme fatale, despite his better judgment. She eventually finds happiness with a younger musician, but in the ironic ending, Joseph does not.

How do you solve a problem like Mary if you are Joseph? You don't; the answers stay hidden. He understands that she is trying to fit into a world that has not come into being yet; that may not exist for a hundred years. Her indecisiveness can thus be explained by the fact that she is trying to inhabit a different reality, as was Dick himself.

Music was an article of faith for Dick. His inclusion of it here as a constant background gives us the author's witnessing presence, presiding over the eternal accompaniment to the dance of the wandering humans.

Being a compendium of reviews of various bookish objects that have somehow thrust themselves into the forefront of my awareness

Thursday, September 17, 2015

Friday, September 4, 2015

A blues-ribbon book

Black Cherry Blues, by James Lee Burke, 1989.

This was the third in the Dave Robicheaux detective series and the first of Burke's books to win the coveted Edgar prize for best mystery novel of the year. By now there are twenty or more titles in the series, and while I have read many of them, oddly I had never read this one before. I found it to be an outstanding representative of the series and certainly deserving of the honor it received. The writing is as deeply felt and vivid and memorable as anything in Burke's oeuvre.

If you have not experienced Burke's prose before, any of his books will do. His models were the great American writers like Hemingway and Steinback, and not so much the genre of mystery fiction. His whole object is to sear you with blazing prose that makes you feel into the recesses of the heart and uncover the true mysteries there that can never be totally solved.

However, the Robicheaux series is special, and if you are approaching it for the first time, I would recommend the first two books of the series, The Neon Rain and Heaven's Prisoners, before you read Black Cherry Blues, as your understanding of the main characters will build consecutively. Still, every title in the series stands alone and it is not necessary to read them in order. This is especially true of the later titles.

In this book, Dave, who has become an ex-cop living in a Louisiana bayou, finds himself accused of a murder he didn't commit, and has to travel to Montana to clear his name. These contrasting milieus provide a canvas for descriptive master Burke to pull out all the stops. This is Louisiana: "Late that afternoon the wind shifted out of the south and you could smell the wetlands and just a hint of salt in the air. Then a bank of thunderheads slid across the sky from the Gulf, tumbling across the sun like cannon smoke, and the light gathered in the oaks and cypress and willow trees and took on a strange green cast as though you were looking at the world through water. It rained hard, dancing on the bayou and the lily pads in the shallows, clattering on my gallery and rabbit hutches, lighting the freshly plowed fields with a black sheen." And Montana: "There were lakes surrounded by cattails set back against the mountain range, and high up on the cliffs long stretches of waterfall were frozen solid in the sunlight like enormous white teeth."

Somehow the shift in scene lets some air into the oppressiveness of the initial chapters and symbolically gives Dave space to redeem himself, at least for this novel. There will be many other opportunities for redemption in the books that follow, for Dave Robicheaux is a mysterious soul whose integrity and self-control dance dangerously on the edge with his propensity for violence. It's a compelling brew which make the reading of these books a compulsive addiction.

This was the third in the Dave Robicheaux detective series and the first of Burke's books to win the coveted Edgar prize for best mystery novel of the year. By now there are twenty or more titles in the series, and while I have read many of them, oddly I had never read this one before. I found it to be an outstanding representative of the series and certainly deserving of the honor it received. The writing is as deeply felt and vivid and memorable as anything in Burke's oeuvre.

If you have not experienced Burke's prose before, any of his books will do. His models were the great American writers like Hemingway and Steinback, and not so much the genre of mystery fiction. His whole object is to sear you with blazing prose that makes you feel into the recesses of the heart and uncover the true mysteries there that can never be totally solved.

However, the Robicheaux series is special, and if you are approaching it for the first time, I would recommend the first two books of the series, The Neon Rain and Heaven's Prisoners, before you read Black Cherry Blues, as your understanding of the main characters will build consecutively. Still, every title in the series stands alone and it is not necessary to read them in order. This is especially true of the later titles.

In this book, Dave, who has become an ex-cop living in a Louisiana bayou, finds himself accused of a murder he didn't commit, and has to travel to Montana to clear his name. These contrasting milieus provide a canvas for descriptive master Burke to pull out all the stops. This is Louisiana: "Late that afternoon the wind shifted out of the south and you could smell the wetlands and just a hint of salt in the air. Then a bank of thunderheads slid across the sky from the Gulf, tumbling across the sun like cannon smoke, and the light gathered in the oaks and cypress and willow trees and took on a strange green cast as though you were looking at the world through water. It rained hard, dancing on the bayou and the lily pads in the shallows, clattering on my gallery and rabbit hutches, lighting the freshly plowed fields with a black sheen." And Montana: "There were lakes surrounded by cattails set back against the mountain range, and high up on the cliffs long stretches of waterfall were frozen solid in the sunlight like enormous white teeth."

Somehow the shift in scene lets some air into the oppressiveness of the initial chapters and symbolically gives Dave space to redeem himself, at least for this novel. There will be many other opportunities for redemption in the books that follow, for Dave Robicheaux is a mysterious soul whose integrity and self-control dance dangerously on the edge with his propensity for violence. It's a compelling brew which make the reading of these books a compulsive addiction.

Labels:

Black Cherry Blues,

Dave Robicheaux,

James Lee Burke

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)